Understanding the Different Forms of Software Testing

Behind every reliable application lies a thorough process of validation known as software testing. Without it, even the smallest coding error could lead to major failures, user frustration, or financial loss. Testing serves as the quality checkpoint that verifies whether a product is both functional and dependable. Since software can fail in multiple ways, testers employ a range of approaches each designed to check different aspects of performance, usability, and security. In this discussion, we’ll look closely at the main types of software testing and why they matter for building high-quality applications. Our Software Testing Online Course equips you with practical skills in functional, non-functional, and automation testing to help you excel in today’s competitive IT industry.

Manual and Automated Testing

When it comes to executing tests, two approaches are commonly used: manual and automated testing.

-

Manual Testing: Testers themselves interact with the application, going through test cases step by step. This helps catch issues with design, usability, or user interaction. However, it is slower and less efficient for repetitive tasks.

-

Automated Testing: Scripts and testing tools are used to run checks automatically. This approach is faster, more consistent, and well-suited for large projects or frequent updates.

In practice, both are used together with manual testing for areas requiring human judgment and automated testing for repetitive or high-volume tasks.

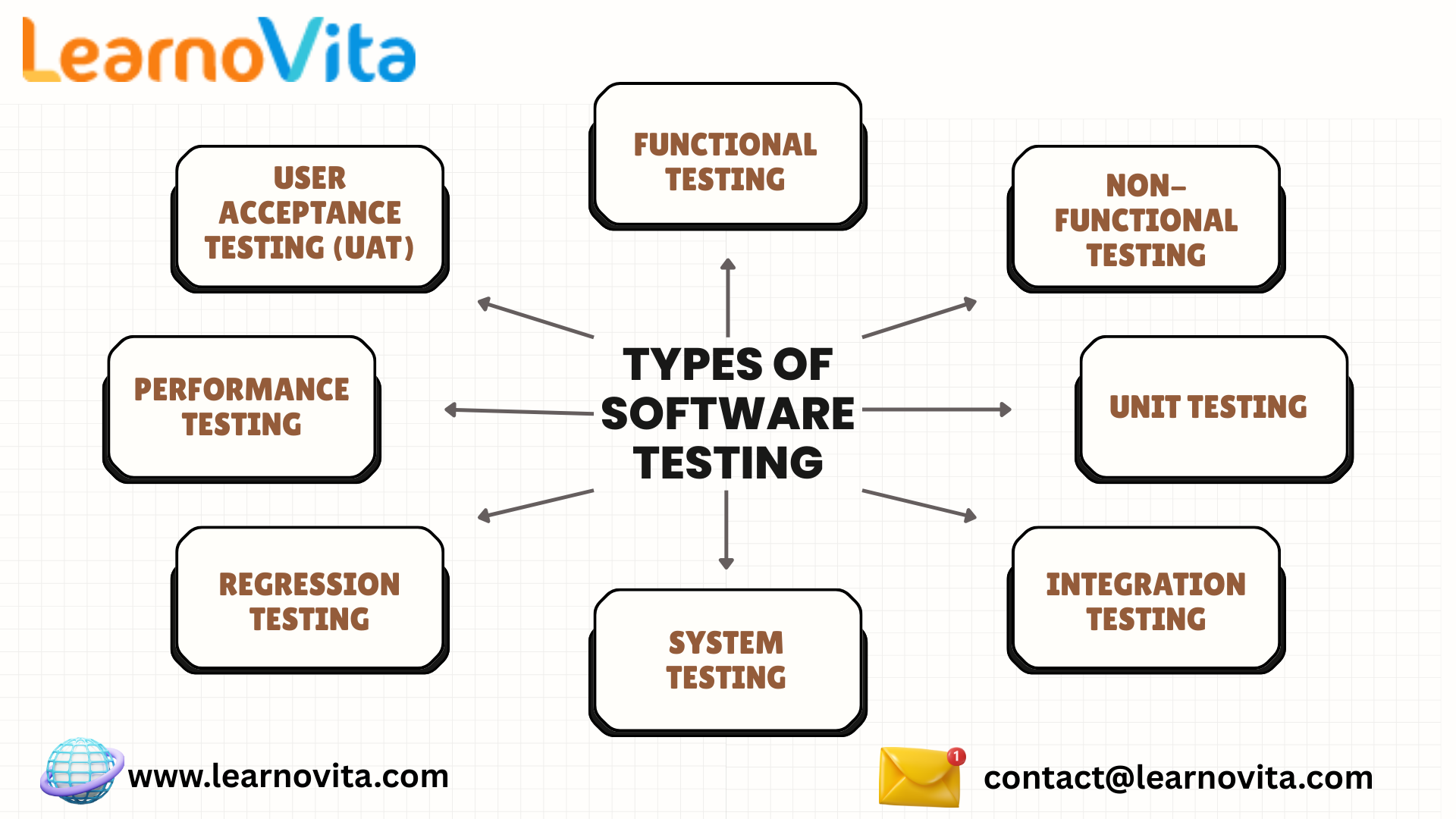

Functional Testing

Functional testing is all about verifying that the software’s features behave exactly as specified. It ensures that the application does what it was designed to do. For example, if an online payment gateway is being tested, functional testing will confirm that a user can successfully add products to the cart, process payment, and receive confirmation. By focusing on requirements, this type of testing reassures both developers and clients that the software delivers on its promises.

Non-Functional Testing

Beyond verifying features, software also needs to perform well under real-world conditions. That’s where non-functional testing comes in. It checks areas like performance, usability, scalability, and security. For instance, a news application may pass functional testing because articles load correctly, but if it takes too long to open during peak hours, users may abandon it. Non-functional testing ensures that an application not only works but also delivers a smooth and trustworthy experience.

Unit Testing

Unit testing examines the smallest parts of code, such as individual functions or classes, in isolation. Developers usually carry out this testing while writing code. The purpose is to catch problems early, before they expand into larger system issues. For example, if a function is designed to calculate discounts, unit testing confirms that it returns the correct value for different scenarios. This practice builds a solid foundation for later stages of testing.

Integration Testing

After individual units are tested, they need to work together without conflict. Integration testing validates the interaction between different modules or services. Consider an online store: the shopping cart, payment system, and inventory database must connect seamlessly. Even if these components work perfectly alone, errors can appear when they interact. Integration testing ensures that the overall workflow is stable and consistent.

System Testing

System testing is a broader evaluation where the entire application is tested as one complete unit. This stage checks whether the software functions as a whole in a production-like environment. For example, in a hospital management system, appointments, billing, patient records, and reports must all work in harmony. By covering the end-to-end process, system testing helps confirm that the product is truly ready for deployment.

Regression Testing

Regression testing is crucial for projects that undergo frequent changes and updates.

Its focus areas include:

-

Verifying existing features continue to work properly after new updates or bug fixes.

-

Leveraging automation tools to speed up repetitive checks and reduce manual effort.

This ensures that enhancements don’t accidentally break older functionalities, maintaining stability as the software evolves.

Performance Testing

Performance testing reveals how the application behaves under varying conditions. It includes several approaches:

-

Load Testing: Assesses performance under expected user traffic.

-

Stress Testing: Pushes the system to its limits to reveal breaking points.

-

Endurance Testing: Observes how the application performs during extended use.

Such testing is particularly important for platforms with heavy traffic, such as video streaming apps or e-commerce portals. Without it, slowdowns or crashes could drive away users. With our Best Training & Placement Program, you’ll gain practical experience and dedicated career support helping you grow your skills and land your ideal job.

Security Testing

Security testing aims to protect sensitive information and prevent unauthorized access. By simulating attacks and probing for weaknesses, it identifies risks before hackers can exploit them. For instance, in an online banking application, security testing ensures that user logins, transaction details, and personal data remain safe. Strong security testing builds user trust and shields organizations from potential damage to their reputation.

User Acceptance Testing (UAT)

User Acceptance Testing is typically the last step before release, performed by the intended users or business representatives. Unlike earlier testing, which focuses on technical correctness, UAT checks whether the software is practical, intuitive, and aligned with business objectives. For example, accountants using a payroll system may confirm that it produces accurate salary slips and complies with tax rules. A green signal from UAT indicates that the software is fit for real-world use.

Exploratory Testing

Exploratory testing offers flexibility by allowing testers to interact with the application freely instead of following pre-defined test cases. By exploring features and experimenting with inputs, testers often uncover defects that structured methods miss. This approach is especially valuable for early-stage products where requirements are still evolving or when creativity and intuition are needed to spot hidden issues.

Conclusion

Software testing is not a single task but a collection of practices, each serving a specific purpose in securing quality. Unit and integration testing strengthen the foundation, system and functional testing validate completeness, regression maintains stability, and non-functional testing enhances performance and reliability. Meanwhile, security testing safeguards data, and UAT confirms business readiness. Exploratory testing adds an extra layer of assurance by capturing unexpected flaws. Together, these methods form a safety net that enables businesses to deliver dependable, user-friendly software. By adopting a balanced mix of testing types, organizations ensure their products meet high standards and remain competitive in today’s fast-moving digital world.

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film

- Fitness

- Food

- Jocuri

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Alte

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness