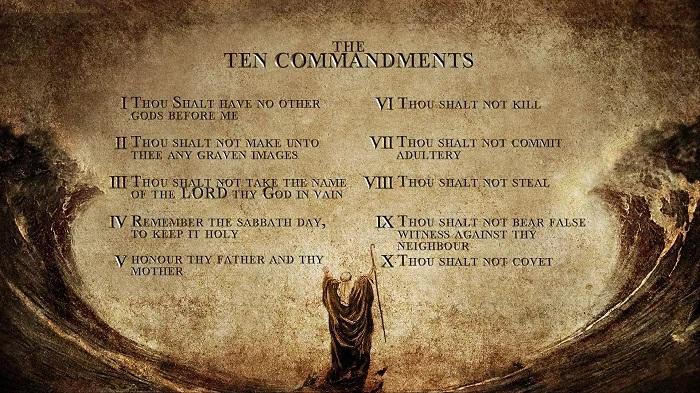

What Does “Thou Shalt Not Kill” Mean in the 10 Commandments?

The commandment “Thou shalt not kill” is one of the most recognized biblical statements in history, yet it remains widely misunderstood. Its placement within the 10 Commandments gives it moral weight, but the language used in older English translations has led to confusion about its true meaning. To understand this commandment accurately, one must explore the Hebrew text, historical context, ancient legal traditions, and the broader theological message woven throughout Scripture.

This article examines the depth behind “Thou shalt not kill,” clarifying what the commandment prohibits, what it does not address, and why its message continues to guide ethical and spiritual thinking today.

The Hebrew Text Behind the Commandment

The Verb Ratsach

The original Hebrew wording of the commandment in Exodus 20:13 is “lo tirtsach,” which is more accurately translated as “You shall not murder.” The key term ratsach refers specifically to the unlawful taking of human life. It conveys intentional, unjustified killing rather than every instance in which life ends by human action.

This distinction is vital. Ancient Hebrew had different words for killing in battle, executing legal judgments, or accidentally causing death. Ratsach is unique in that it always implies moral guilt, personal malice, or severe negligence.

Why Early English Bibles Said “Kill”

The King James Version rendered the commandment as “Thou shalt not kill,” not because translators misunderstood the Hebrew, but because English usage in the 1600s was broader and less precise than today. “Kill” often carried the meaning “murder,” and the nuance was clear to its original readers. Over time, however, modern English evolved, leading many to misinterpret the command as a blanket prohibition against all forms of taking life.

Understanding the Ancient Legal Context

Israel’s Legal Structure

To interpret the commandment correctly, it must be situated within the wider legal framework given to ancient Israel. The same Torah that contains this command also includes laws concerning capital punishment, accidental manslaughter, self-defense, and warfare. Because these laws coexist alongside Exodus 20:13, it is evident that “Thou shalt not kill” was not meant as a universal ban on taking life in all circumstances.

Cities of Refuge and Unintentional Killing

Numbers 35 and Deuteronomy 19 explain that when someone caused death unintentionally, they could flee to a city of refuge for protection until due legal process was carried out. These laws demonstrate that not all forms of killing carried equal moral weight. The commandment targeted deliberate murder, the shedding of innocent blood, and violent intent.

Protecting the Value of Human Life

The commandment sits at the heart of a broader theological message: human life is sacred because humans bear the image of God. Murder is not just a crime against a person; it is an attack on the divine image itself. This spiritual reality elevated the seriousness of the offense in the eyes of ancient Israelites and provided the foundation for the commandment’s firm prohibition.

How the Commandment Evolved in Jewish and Christian Interpretation

Rabbinic Understanding

Jewish scholars have long viewed the commandment as the ultimate moral boundary. Rabbinic literature emphasizes that murder is one of the three sins a person must never commit even to save their own life. The rabbis also stressed the importance of intention: premeditated killing fully violates the commandment, while accidental death is tragic but not morally equivalent.

Early Christian Perspectives

Jesus expanded the meaning of the commandment in Matthew 5, teaching that anger, hatred, and contempt toward others violate the spirit of the commandment even if no physical harm occurs. For early Christians, the prohibition against murder became a call to cultivate peace, reconciliation, and respect for all people.

Church Tradition and Ethical Debates

Throughout Christian history, theologians have debated how the commandment applies to warfare, capital punishment, and self-defense. While interpretations differ among traditions, all agree that the commandment establishes the sanctity of life and condemns intentional murder.

What the Commandment Does Not Prohibit

Self-Defense in Biblical Thought

The Bible distinguishes between self-defense and murder. Exodus 22 describes a situation in which a homeowner defends against a thief breaking in at night. If the intruder dies during the struggle, the homeowner is not automatically guilty of murder. This scenario shows that killing in self-defense does not fall under the prohibition of ratsach when the defender did not act with murderous intent.

Warfare in the Old Testament

The Old Testament includes accounts of warfare that do not violate the commandment. These were viewed as acts of national defense or fulfillment of divine instruction. While these passages raise complex ethical questions, they were never considered acts of murder according to ancient Israelite law.

Judicial Punishment

Capital punishment existed within Israel’s legal system for severe crimes. While interpretations vary today, ancient Israelites saw legal execution as a societal protection, not an act of murder. Thus, the commandment does not prohibit all state-imposed penalties in its original context.

The Commandment’s Moral Purpose

Preserving Community

At its core, the commandment protects the stability and safety of the community. Murder destroys families, erodes trust, and unravels social bonds. By forbidding murder, the commandment preserves the cohesiveness and functioning of society.

Affirming Human Dignity

The commandment affirms that every human life possesses inherent value. Ancient cultures varied in their moral codes, but Israel’s commandment gave absolute protection to human beings regardless of social class. This equality before divine law distinguished Israel from many surrounding nations.

Cultivating a Heart of Peace

Jesus and early Christian writers understood the commandment not only as a legal boundary but as a spiritual discipline. Avoiding murder is the beginning, not the end, of moral transformation. True obedience requires uprooting anger, bitterness, and dehumanization before they grow into violence.

Why the Commandment Still Matters Today

Ethical Clarity in a Violent World

Modern societies grapple with violence, warfare, crime, and systemic injustice. Understanding what “Thou shalt not kill” actually means helps individuals and communities evaluate these issues with greater moral clarity. The biblical prohibition against murder remains a necessary foundation for ethical reasoning.

Personal Responsibility and Spiritual Growth

The commandment invites self-reflection. It challenges individuals to consider how their attitudes, words, and actions reflect respect for human life. While anger or resentment may not lead to physical harm, they can still violate the deeper essence of the commandment.

The Guiding Voice of the 10 Commandments

Because this commandment is part of the 10 Commandments, its message carries enduring significance across cultures and traditions. Whether viewed religiously or philosophically, it forms a universal moral boundary that helps maintain the value of life and the structure of society.

Conclusion

“Thou shalt not kill” is not a vague or simplistic rule but a deeply nuanced moral principle rooted in Hebrew language, ancient legal tradition, and the theological understanding of humanity’s sacred value. It specifically prohibits murder—the intentional, unjustified taking of human life—while allowing for the complexities of self-defense, societal protection, and justice. Seen through the broader lens of Scripture, the commandment calls not only for restraint from violence but also for the cultivation of peace, dignity, and compassion. Its message remains profoundly relevant, reminding us that the protection of life lies at the heart of the divine vision for human flourishing.

- Art

- Causes

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film

- Fitness

- Food

- Jeux

- Gardening

- Health

- Domicile

- Literature

- Music

- Networking

- Autre

- Party

- Religion

- Shopping

- Sports

- Theater

- Wellness